By Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

This November, just like every time that new sanctions are levelled on North Korea, the first question tends to be: what will China do? Unsurprisingly, the same question followed after UN resolution 2270 in March this year, when the international community adopted the strongest sanctions against North Korea to date, most crucially targeting its minerals exports. This time, some believed, would be different. China was finally fed up and would take measures to hit North Korea’s economy, and official; statements and some bureaucratic action reinforced this impression. Now, some hope that the “cap” measure on imports of North Korean coal will remove the loophole created by the “humanitarian exemption” in the previous sanctions.

By now, after the THAAD, other geopolitical developments and the sheer passing of time, the question of China’s degree of sanctions enforcement has almost faded into the background. As the Washington Post’s Anna Fifield showed in a dispatch from Dandong a few weeks ago, sanctions are at most one factor among many that impact trade between China and North Korea.

This summer, I visited Dandong, Yanji and Hunchun, three Chinese cities along the border. I got a very similar impression: sure, some people involved in border trade told me, things had gotten a little more complicated, though not much. But sanctions were rarely mentioned as the reason for any added difficulties or downturns in trade. At the time, China’s enforcement of sanctions was very much a topic of debate, and most analysts were skeptical of any squeezing going on, while some claimed trade had virtually ceased. At my visit, on the contrary, I saw fairly vigorous trading activity, and few people I spoke to thought any changes had occurred since sanctions were enacted. Posting these impressions and pictures has been a project in the pipeline for a while, so while much has happened since this summer regarding China-DPRK relations and trade, I hope that the reader will find it interesting to see how things looked at a time when some concluded that China was finally squeezing North Korea in a way that hurt. To be clear: all impressions and pictures below are from late June of 2016.

Trailing the China-DPRK border, in search of sanctions

Dandong

Entrance to the Dandong customs inspections area. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Earlier this year, the UN Security Council adopted the strongest sanctions that North Korea has faced to date. As with previous rounds of sanctions, one of the major questions is China’s degree of enforcement. Going back a few months, some suggested that major shifts had taken place, and that trade between North Korea and China had declined radically.

By the actual border, this summer, things looked very different. In contrast to the image of a desolated trading environment, I encountered bustling traffic during a visit earlier in the summer. During one morning in late June, around 85 trucks crossed the border from North Korea into China in only about one and a half hours. Virtually all trucks were registered to northern Pyongan province, the home province of Sinuiju. In addition, 19 cars and buses, one long freight train and one passenger train crossed the bridge during the same time. After this first stint of traffic, the flow reversed and a steady flow of trucks began pouring into North Korea from China. Only during the 15 minutes when I observed the traffic going from China, into North Korea, 35 trucks and 13 buses and cars crossed the bridge.

The traffic flowed in sequences, one direction at a time. And this was only the morning traffic. The flow may have continued throughout the day, as the traffic moved in intervals. Walking back to the customs area from the bridge crossing in the early afternoon, what was previously a calm intersection by Chinese inner-city standards had turned busy: trucks lined the entire street leading up to the customs office and some flowed over into the adjacent street, waiting to drive into the inspection area. All in all, more than 80 trucks lined the roads waiting to cross into North Korea. Most carried Chinese license plates.

Trucks lined up on both sides of the street at one of the main intersections in central Dandong, waiting to go into the customs inspection area to cross into North Korea. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Trucks, trucks and more trucks. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Trucks lined up for customs inspection along the streets of Dandong before crossing into North Korea. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Trucks lining up for customs inspection before crossing into North Korea from Dandong. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

The never-ending line of trucks. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Truck driving into the Dandong customs area. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Another picture of the never-ending line of trucks. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

North Korean trucks crossing into Dandong from Sinuiju. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

It is commonly estimated that around 200 trucks go between China and North Korea on a regular day. In sheer numbers, virtually nothing seemed to have changed regarding the traffic since the latest round of sanctions. Only the trucks observed in plain sight during this morning amount to a little under 200, and this merely during the first few hours of the day. At least 10–20, probably far more, were already in the customs inspection area waiting to cross. In short, things looked very regular and busy.

Trucks waiting to cross from North Korea into Dandong. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Some of the trucks going into Dandong from Sinuiju looked empty. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Of course, one must be careful not to draw too drastic conclusions from one day of observations. Things may have changed throughout the summer and surely during the fall, and channels such as ship transports are not visible from the border bridge area. Moreover, according to reports from inside North Korea, the authorities have expressed concerns about potentially shrinking trade volumes as a result of sanctions, and some traders now smuggle goods that are covered by the sanctions rather than transporting them openly, as they have in the past, according to Daily NK. In short, sanctions did appear to be having some degree of impact, even during the past summer.

Most North Korean trucks crossing into Dandong were registered to North Pyongan province ( 평안북도도, here abbreviated to 평북), the province bordering Dandong. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Another truck registered to North Pyongan province. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

However, the truck traffic across the Chinese border through Dandong suggested that the picture was mixed. At the very least, observations from the border area showed that even though trade in certain goods may have gotten more difficult, North Korea was by no means economically cut off from China, and still is not. Prices for food and foreign currency on North Korean markets, too, remained relatively stable through the summer from when sanctions were put in place, indicating that the economy as a whole is not feeling any drastic impact of the sanctions.

Factory materials going into North Korea from China. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Factory materials going into North Korea from China. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Most trucks transporting factory materials into North Korea appeared to be Chinese-registered. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Another Chinese truck transporting factory materials into North Korea. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

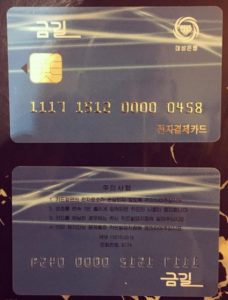

If the North Korean economic elite was worried about the sanctions, it certainly did not show at one hotel in central Dandong. Sinuiju in North Korea is only a few minutes drive over the Yalu River, on the bridge connecting the two countries. The hotel was packed with North Korean guests, many of whom have presumably come over for purchasing and meetings with Chinese business partners. They came and went in a steady stream, wearing luxury brand clothing, watches and carrying expensive bags and wallets.

They paid everything in cash, and at least one person per travel party spoke Chinese. One man held a car key with a logo from KIA, the South Korean car manufacturer. One woman sported a Hello Kitty handbag. As some got ready to depart, bags piled up in the lobby, seemingly filled with goods from shopping sprees around town. Some of it seemed to be meant for re-sale in North Korea. Many stores around the flood banks cater specifically to a North Korean clientele, and sell items like kitchenware that are not easily accessible across the river.

Many stores in Dandong cater specifically to North Korean consumers. The sign at the left bottom of the picture reads “조선백화점,” translating into “Korea department store.” Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Travelling to Dandong, it was particularly apparent why the Chinese government would be reluctant to clamp down too hard on border traffic, even if it would want to do so. Political reasons aside, trade between North Korea and China matters for cities such as Dandong. One can see it in the flesh: the streets are packed with companies dealing in imports and exports to and from North Korea. One company trades steel; another sells construction equipment such as tractors. Several sell cars and buses, and others deal in refrigerators, dishwashers, washers and dryers. One, called “Pyongyang Tongshin (평양통신),” judging by its name, offers cell phone services for traders travelling into North Korea. Should trade between the two countries drastically dive, the local economy would take a hit.

Advertisements for North Korean cell phone service Koryolink in Dandong. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

“Pyongyang Communications.” Sign in Dandong. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

One could turn these observations on their head: if so many trucks were lining up and only moving slowly into the customs area, could that not mean that inspections had gotten tighter? Was the line of trucks actually a sign that Chinese authorities did what they have promised to do?

Perhaps. But not according to people around the border crossing and customs area. I asked several individuals involved in the cross-border trade about the long lines and waiting times for border crossings. No one seemed to believe that the traffic commotion and lines were anything out of the ordinary. Both Chinese and North Koreans involved in import-export business said traffic had not changed at all during the past year or so. Overall trade had declined a bit, one person said. The trucks carried a little less than they did before, but only marginally. Coal was not traded as frequently as it was before the sanctions were put in place.

This sign lists services for one Dandong firm that offers, among other things, UPS transport services and solar-powered appliances, which have become popular in North Korea in recent years. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

But the timing of the early 2016 round of sanctions made such statements difficult to assess. China had in fact been decreasing its coal imports from North Korea at different points in time several years before the latest round of sanctions. Between 2013 and 2015, for example, the value of Chinese coal imports from North Korea shrank by almost 25 percent. Only between January and February 2014, the value of trade between the countries dropped by 46 percent. The statistics are often clouded by the fact that global market prices for commodities such as coal fluctuate heavily. There may also be a variety of seasonal factors at play. In sum, isolating sanctions as a variable is notoriously difficult, and often, numbers do not tell the full story. As of June this year, North Korean coal could still be ordered through the Chinese online shopping mall Alibaba.

Moreover, even if Chinese authorities wanted to check all goods cross with minute rigidity, one can question whether it would even be practically feasible. The customs area is not particularly large and did not appear to be overflowing with staff. Checking around 200 trucks per day for their exact goods, and determining whether its revenues could be used to fund North Korea’s weapons program – the condition stated by the latest sanctions – seems like a gargantuan task in practice.

Hunchun

Tourists and a truck waiting by the Hunchun-Rason border crossing (Quanhae). Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

The Dandong-Sinuiju is the main point of trade between China and North Korea, but not the only one. An one-hour drive from the Chinese city of Hunchun, trucks and people come and go to and from the North Korean northeast. At the border crossing, most seem to be going to the special economic zone in Rajin in North Korea. On one gloomy Thursday in late June, around 40 Chinese trucks waited to cross. One Chinese-Korean waiting for the gates to open to the customs area told the present author that business is going very well these days. He runs a hotel in Rajin, catering mostly to Chinese tourists and business people. He has seen no dip in customers over the past year – rather, more people are coming than before. This single testimony may not be fully indicative of trade as a whole, but it does suggest that Chinese tourism remains an important and fairly viable source of revenue for North Korean businesses in Rason.

The Quanhae border crossing from afar. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Trucks lining up to go into North Korea. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

More trucks at Quanhae. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Trucks at the border crossing. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Chinese tourists lining up to have their passports checked before heading into Rason. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

This was certainly the way things looked at the border crossing. Chinese tourists came and went in great numbers, many carrying North Korean shopping bags. Trucks, too, continuously crossed the border throughout the afternoon. All in all, 80–100 trucks drove into North Korea during this afternoon. One was adorned with a logo from the Dutch shipping company Maersk. A few trucks came out of North Korea as well, many seeming to carry seafood destined for cities such as Hunchun and Yanji.

A truck adorning a logo from the Dutch shipping company Maersk having just crossed into North Korea from Hunchun. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

In addition, a large number of buses and minivans carrying tourists and traders went in from China. Many minivans carried driving permits for Rajin clearly visible through their front windows. Given the amount of truck traffic only during the afternoon, it seems a reasonable estimate that perhaps twice the amount of traffic went through during the day as a whole. One person with good knowledge of the border area estimated that around 200 trucks go through at this crossing on a regular day, though this figure is obviously neither exact nor certain.

Customs office on the North Korean side of the border crossing. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Chinese tourists waiting to head into North Korea. Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

The two bridges connecting Rason to China (particularly the newly constructed one in the back). Photo: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

These observations did not fully prove that China was not enforcing sanctions on North Korea during the summer of 2016. However, they did show that trade and traffic between the countries was still very much alive. Some goods may have be traded less, but neither sanctions nor souring relations between North Korea and China seemed to have reduced trade as much as some observers have claimed. The North Korean economy may be impacted by sanctions, but it is not and rarely has been fully isolated from the rest of the world.