By Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

This certainly has been the season of contradictory information on North Korea’s food supply. The North Korean government is celebrating and claiming success of their agricultural reforms, while the FAO reports that things have gotten worse. Let us recap what has happened:

First there was the drought. North Korean state media described it as the worst one in 100 years. UN agencies predicted large-scale crop failures and appealed for food aid, warning that large shares of the population would be at great risk if aid did not come. The UN’s emergency response fund (CERF) allocated $6.3 million to counter the impacts of the drought. The rains came, however, and the drought alarms seemed to have been exaggerated.

Next, the North Korean media – assuming you can even talk about it as a single, coordinated entity – went the other direction. In July, the weekly Tongil Sinbo claimed that thanks to agricultural reforms, this year’s harvest had actually increased “despite adverse weather conditions”.

And recently, reports turned the other way again. In early September, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN declared that the cereal production forecast for the main season of 2015 had declined drastically from last year due to a “prolonged dry spell”.

The rain that eventually came in July and August, causing flooding in the northern parts of the country and leading to an estimated loss of one percent of all planted areas. The FAO rice production forecast for 2015 is 12 percent below that of last year. State food rations, the importance of which can be debated, declined drastically, according to the agency.

In the midst of all of this, North Korean propaganda is still claiming success for the reforms. Earlier this month, the state news agency KCNA reported that a “dance party” had been held in South Hwanghae, part of the country’s rice bowl, celebrating improving conditions on the countryside:

The performers presented cheerful dances depicting the happy agricultural workers who work and live in the rural areas now turning into a good place to work and live thanks to the successful embodiment of the socialist rural theses under the leadership of the Workers’ Party of Korea.

The picture gets even more complicated if one assigns meaning to the fact that cereal imports from China were reportedly lower in July this year compared to 2014. Figures from just one month might not indicate a trend, but given that July was a particularly dire month, these figures are still significant. If imports are being decreased because the official line is that agricultural conditions have improved, no matter the reality, that might be bad news for those in the North Korean public that rely on the public distribution system for any significant part of their consumption.

Either the FAO is right and the North Korean government wrong, or the other way around. Harvests this season cannot have been improving and getting worse at the same time. The FAO is probably far more likely than the North Korean government to have made a correct assessment here. Even if North Korean authorities aren’t claiming success of the reforms for propaganda reasons – which they may well be doing – it is hard to see why their statistical and monitoring capabilities would be better than those of the FAO.

So, the North Korean government is claiming that agricultural reforms are leading to better harvests and food conditions, even when they probably aren’t. Why would they do that? There are lots of possible reasons and one can only speculate.

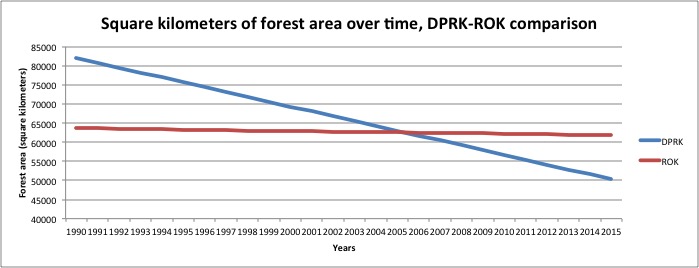

One possible reason is that the agricultural reforms have become a prestige project. North Korean propaganda channels and news outlets have publically claimed that reforms are being implemented and leading to good results, even though some adjustment problems have been admitted. The same pattern, by the way, can be seen with regards to forestry policies – state media has publicized them with a bang and claimed that they just aren’t being implemented well enough by people on the ground when they don’t seem to be working as intended.

This could be an indication that agricultural reforms are indeed, like many have assumed, a major policy project of Kim Jong-un and the top strata.

That could be good news. After all, North Korea is in dire need of changes in agricultural structures, production methods, ownership and responsibility.

But it could also be bad news. When policies are strongly sanctioned and pushed by the top, their flexibility is likely to be inhibited. In other words, if the top leadership says that something should get done, it has to get done regardless of whether it works well or not.

Again, look at the forestry policies. According to reports from inside the country, those tasked with putting the new policies into practice on the ground say that doing what the central government asks isn’t smart or possible. Nevertheless, such orders are hard and risky to question.

At this stage it is only speculation, which is always a risky endeavor when it comes to North Korea. It may well later turn out to be wrong.

But if the state is placing enough prestige in the agricultural reforms to claim that conditions are improving even if they aren’t, that may lead to limited flexibility in how they are implemented and changed in the future. In other words, if the leadership thinks they are important enough to claim success even when things are getting worse, they may not be prone to changing their orders to fix what isn’t working.