By: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

There’s been a few reports over the past few weeks about panic buying in Pyongyang, particularly of imported goods. The foremost reason appears to be the government’s restrictions of imports, aside from essential goods (whatever these are). A quick thought:

On the one hand, on a closer reading beyond the term “panic buying”, it’s apparent that we aren’t really talking about fundamental, daily necessities for the most part, but about imported items such as batteries and certain vegetables. When we monitor economic developments for social stability, such analyses tend to focus on items like rice and, at least in countries other than North Korea, fuel, and not least the stability of the currency. So it may not matter all that much if people in a northern province cannot buy lighters imported from China, or if Pyongyangites can’t buy imported pepper and other non-staple goods. (As you will see in one of the articles below, Daily NK has not heard reports of panic buying in Hyesan at all.)

At the same time, however, these imported goods are quite essential in the everyday lives of many people. We don’t know how much of imported goods the average person consumes, and I suspect it’d differ greatly between provinces. Since at least a significant proportion of the population consumes imported goods on a regular basis, these difficulties in acquiring items imported from China would in many cases cause great annoyance and, in others, disrupt production processes of firms and industries, although some exceptions are granted for “essential” items. Who determines what’s essential is likely hinges on political and economic clout, and it certainly won’t be the mom-and-pop-shops of the backstreet markets.

I’ve gathered a few related articles here. AP wrote about the topic on May 7th, 2020, with intelligence sources in Seoul confirming the news:

The NIS said it cannot rule out a virus outbreak in North Korea because traffic along the China-North Korea border was active before the North closed crossings in January to try to stop the spread of the virus, according to the lawmaker.

The NIS declined to confirm Kim’s comments in line with its practice of not commenting on information it provides to lawmakers. Kim did not discuss how the NIS obtained its information.

Last Friday, Kim Jong Un ended his 20-day public absence when he appeared at a ceremony marking the completion of a fertilizer factory near Pyongyang. His time away triggered rumors about his health and worries about the future of his country.

The NIS repeated a South Korean government assessment that Kim remained in charge of state affairs even during his absence. His visit to the factory was aimed at showing his resolve to address public livelihood problems and inject people with confidence, Kim Byung Kee cited the NIS as saying.

The NIS said the virus pandemic is hurting North Korea’s economy, mainly because of the border closure with China, its biggest trading partner and aid provider. China accounts for about 90% of North Korea’s external trade flow.

The trade volume between North Korea and China in the first quarter of this year was $230 million, a 55% decline from the same period last year. In March, the bilateral trade volume suffered a 91% drop, the NIS was quoted as saying.

This led to the prices of imported foodstuffs such as sugar and seasonings skyrocketing, Kim Byung Kee quoted the spy agency as saying. He said the NIS also told lawmakers that residents in Pyongyang, the capital, recently rushed to department stores and other shops to stock up on daily necessities and waited in long lines.

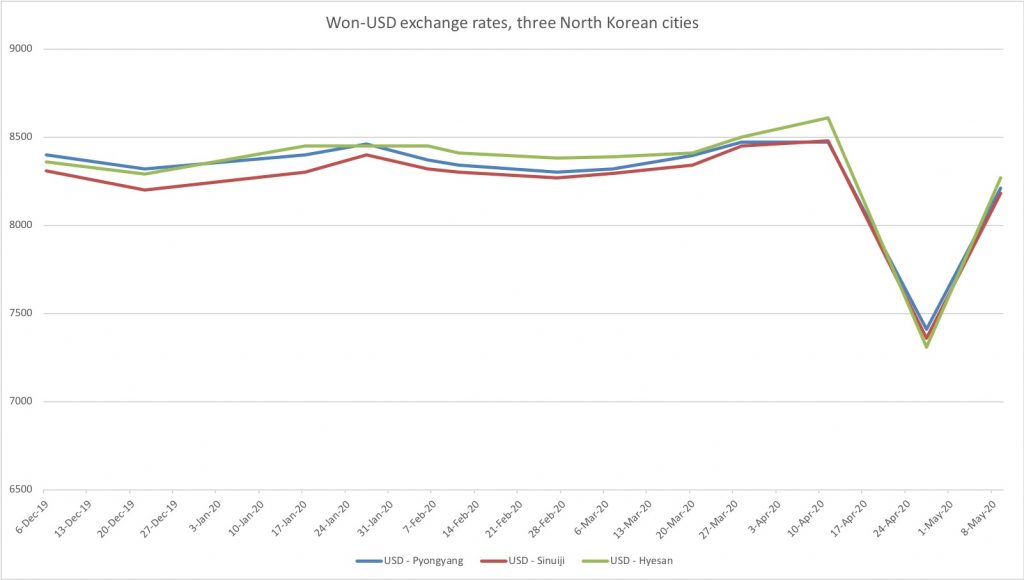

The NIS said prices in North Korea “are being stabilized a little bit” after authorities clamped down on people cornering the market, Kim said in a televised briefing.

(Source: “Seoul reports panic buying in N. Korea amid economic woes,” AP/Mainichi, May 7, 2020.)

NK News was one of the first outlets to cover the topic, in an article on April 22nd:

“Panic buying” sprees have been spotted taking place in some of Pyongyang’s stores and groceries since Monday, multiple informed sources told NK News, resulting in increasingly empty shelves and a growing shortage of key staples.

It’s unclear what’s led to the sudden surge in demand, with one source describing empty shelves and a sudden absence of staples like vegetables, flour, and sugar.

Locals have been buying “whatever is there,” one expat said, saying that “you can hardly get in” to some stores.

Both the expat and another person in Pyongyang said the surge was particularly notable on Wednesday.

Another source said large groups of locals were seen buying big amounts of mostly-imported products in some grocery stores, resulting in abrupt shortages.

(Source: Chad O’Carroll, “North Koreans “panic buying” at Pyongyang shops, sources say,” NK News, April 22nd, 2020.)

Daily NK, of course, has reported extensively on the topic, from both Pyongyang and the provinces. Imported goods are not only consumed in Pyongyang:

“The prices of Chinese goods have risen sharply in markets across the province, including the Yonbong and Wuiyon markets in Hyesan,” a Ryanggang Province-based source told Daily NK on Apr. 28.

According to the source, the price surge has mainly affected Chinese products, including daily necessities such as sugar, flour, and other cooking products.

For example, the price of Chinese seasoning has increased fourfold to a KPW 40,000 (around USD 6). Flour, rice and other grain prices have also increased. Two weeks ago, imported Chinese rice was being sold at KPW 4,400 per kilogram but is now being sold at KPW 5,500.

The price hikes have not just affected food. Chinese cigarettes have also increased in price: a box of Chinese-made Chang Baishan cigarette packs, for example, which used to cost KPW 12,000, is now KPW 17,000.

“Even Chinese lighters, which usually cost around KPW 700, have seen a price hike of nearly threefold and now cost KPW 2,000,” the Hyesan-based source added.

The main reason for these price surges is the halt in Sino-North Korean trade following the closure of the North Korean-Chinese border in late January. The effects of the steep fall in Sino-North Korean trade were made clear in recent data published by China’s General Administration of Customs. According to this data, Chinese-North Korean trade in March dropped by 91.3% compared to the same period last year to just USD 18.64 million.

“Just two weeks ago merchants were feeling more optimistic given the improved situation in China. Now, they’ve lowered their expectations quite a bit,” the Hyesan-based source told Daily NK, adding, “Prices are rising because business people are intentionally sitting on their stocks with the hope that prices will increase even more.”

[…]

Meanwhile, Daily NK is unaware of any reports of panic buying in Hyesan [emphasis added].

(Source: Kang Mi Jin, “Ryanggang Province witnesses price spikes,” Daily NK, April 30th, 2020.)

And, more recently, a report from Pyongyang:

“There are a lot of ordinary stores that have closed or are unable to sell anything because they have no stock left,” a Pyongyang-based source told Daily NK on Apr. 30. “Right now 100 grams of imported pepper costs KPW 40,000, 450 to 500 grams of MSG costs KPW 48,000 and sugar can’t be found at all.”

PRICE SPIKES

The prices of imported food items nearly doubled after Apr. 17, when the North Korean government announced restrictions on imported goods deemed “unnecessary” for the North Korean economy. Prices began to rise rapidly once more before the publishing of this article in Korean on May 1.

According to Daily NK’s Pyongyang source, the price of imported pepper was just KPW 8,000 per 100 grams before the announcement, but doubled to KPW 16,000 after the decision was released. Now, the price has reportedly risen to KPW 40,000.

“The price of watch batteries and other small batteries for common household appliances like remote controllers for TVs have tripled or quadrupled,” the source further reported. “The price of batteries had remained stable even after the announcement, but several days ago it started to rise suddenly. The spike is probably because so many people began hoarding them.”

Although the price of batteries has risen to an unprecedented degree, Pyongyang residents reportedly continue to buy them in bulk, in boxes of 50, and as much as 10 boxes at a time. The hoarding is likely due to concerns that the price will only continue to rise and that soon there may not be any batteries left to buy.

“Many of the electronics stores throughout the city have closed down,” the source said, adding, “Stores that still have stock have closed perhaps because of rumors that Chinese products will no longer enter the country.”

In short, the source’s report suggests that state-run electronics stores, which command 20% of the market, have no stock left, while privately-run stores that take up the remaining 80% of the market have closed up despite still having stock on hand.

Based on the source’s report, owners of privately-run stores may have closed down their shops with the intent to sell their goods at prices even higher than they are now. The owners are likely under the belief that the recent import restrictions announcement means that various electronics accessories will no longer enter the country from China for some time.

(Source: Ha Yoon Ah, “Pyongyangites continue to hoard as prices keep rising,” Daily NK, May 4th, 2020.)