By: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Recently, the BBC became one of few global outlets to succeed in interviewing ordinary North Koreans inside the country about the food situation. The image is dire: starvation, empty markets and other signs of severe food shortages.

In the past few years when reports of food scarcity have surfaced from North Korea, market prices have given remarkably little credence to the claims. Not so at the moment. Comparing current prices levels with historic ones, the overall picture suggests that prices since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic (and the North Korean government’s border closure), market prices have moved to a permanently higher level, indicating that overall supply of food is lower. This does not give us a specific number on how severe the food shortage is, but it gives quantitative evidence that food has become significantly scarcer since the onset of the pandemic.

To show this, I use market price data gathered and reported by Rimjingang, an online news outlet with sources inside North Korea that regularly publish market prices. I chose this specific data set because it is transparent and specific about where in the country the data comes from. Due to tightened border controls under Kim Jong Un’s tenure, information from inside North Korea has become even more difficult to access. Therefore, transparency about the data is crucial.

The price data almost exclusively comes from the region bordering China, such as Ryanggang and North Hamgyong provinces. The border region is different from the rest of the country in several crucial respect, perhaps most crucially in that it is much more involved in trade and smuggling with China than other regions. Nonetheless, the North Korean market system is integrated to some extent, with goods being transported around the country for sale. Although dilapidated infrastructure and harsh state regulations make internal travel difficult, the overall price trends very likely hold for the national level.

Market changes after Covid-19

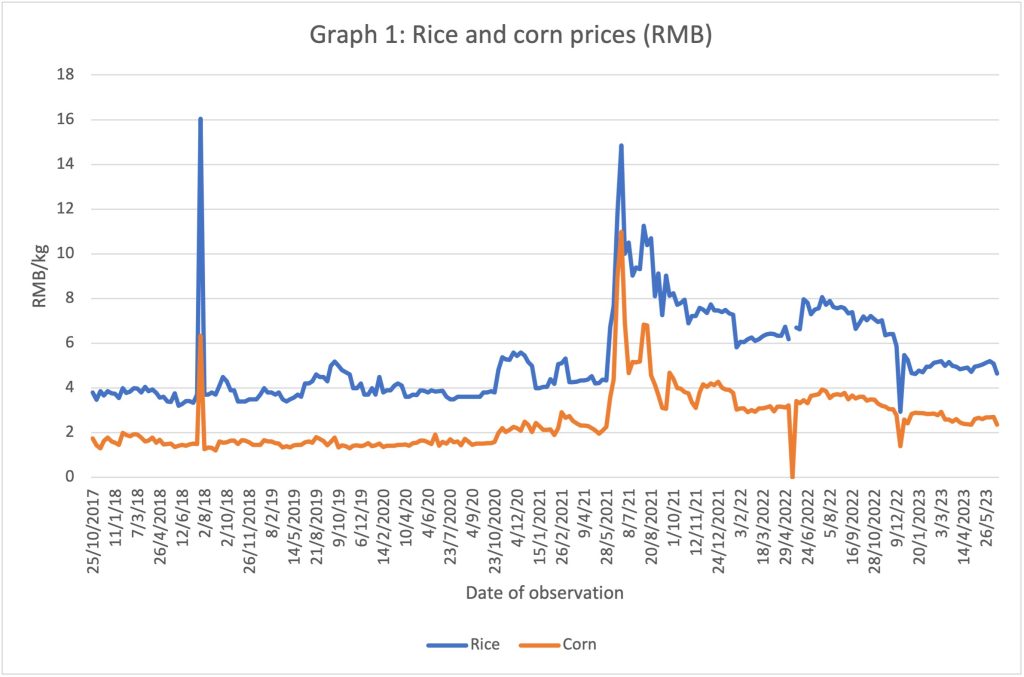

Prices fluctuate frequently on North Korea’s markets, but usually within a more or less fixed span. The following graph shows prices for North Korea’s two main staple goods, rice and corn, from 2017 until mid-June this year. The prices are shown in renminbi, the most commonly used foreign currency in the border region, to check for inflation in the North Korean currency, Korean People’s Won (KPW).

The left side of the graph shows prices before Covid-19. Aside from a few nonsignificant bumps, prices hovered between 1–1.5 RMB for corn and 3.5 RMB for rice for the most part prior to the inception of the pandemic, fluctuating throughout the year. Interestingly, although North Korea closed its borders in January 2020 to protect against the virus, prices don’t truly begin to move until October that year.

Over the course of the next few months, however, prices for both rice and corn climbed significantly.

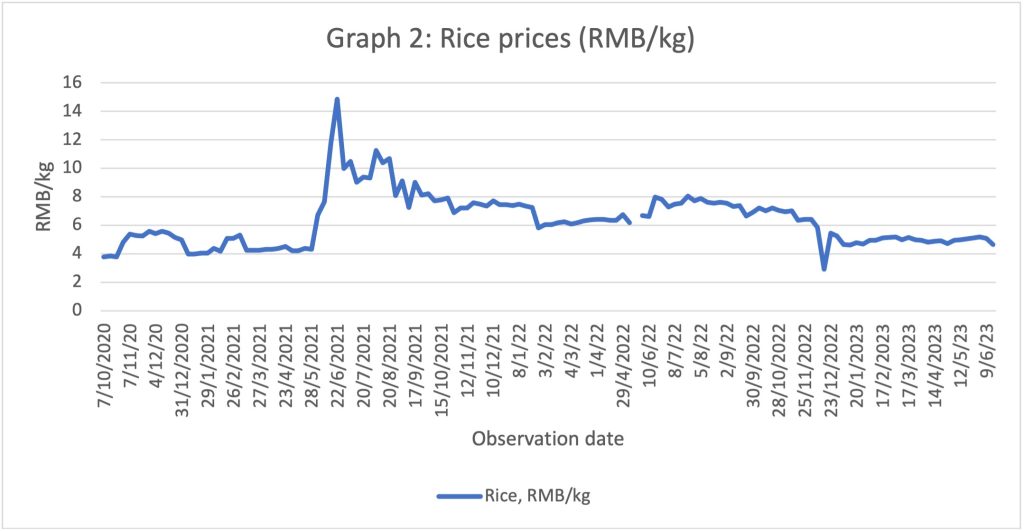

Rice prices rose from their regular level to move between 4 and close to 6 RMB in late 2020 and early 2021 and shot up drastically during the spring and summer months, the lean season before the fall harvest, when the storage of food begins to dry up. Prices normally go up during this season, but perhaps a spreading awareness that the border wouldn’t open anytime soon pushed prices up much further than normal. After shooting up to close to 15RMB and remaining much higher than normal for several months, prices stabilized at an interval between 8 and 4.5–5 from the fall of 2021 and onward. Prices have been moving around 5RMB since the end of 2022. That is an approximate 1.5RMB difference from the normal price level, or 42 percent.

On the one hand, prices now are much more stable than last year’s fluctuations to very high levels. On the other hand, the price level is now permanently higher, meaning that North Korean consumers face a permanently higher price level. Higher prices, logically, suggest that supply has dropped. In other words, with food supply lower, people must pay significantly more for the same amounts of food.

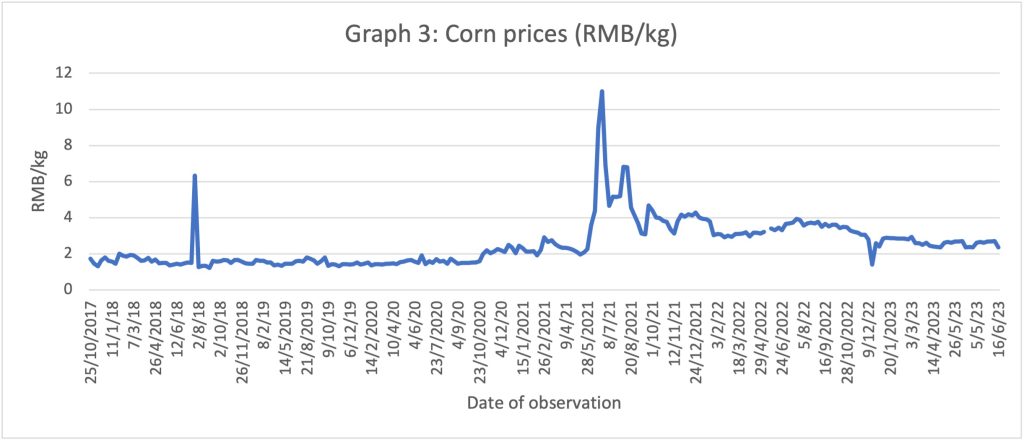

We see the same dynamics in prices of corn. Graph 3 below show corn prices from the fall of 2017 until the latest observation in mid-June:

Corn is a generally less preferred staple good for North Korean consumers, meaning that people tend to increase their consumption of corn when food overall becomes more expensive. From moving around 1.5RMB/kg before the pandemic, corn prices climbed significantly from late 2020, hitting almost 3RMB – a doubling of the normal price level – by March 2021. Prices then climbed further during the rest of the year and hovered around 4RMB in the late summer and fall. Since late 2022, prices have moved between 2.3 and close to 3RMB, meaning they have increased by at least more than half on the lower end of the spectrum, and doubled for the higher end.

Conclusion

None of this is evidence of a widespread famine in North Korea, and the BBC’s three eyewitness testimonies also do not fully prove anything of the sort. But that the country is experiencing a significant food shortage seems beyond doubt, as suggested both by reports from people inside the country as well as market prices. These prices do not tell the full story. The situation likely varies significantly between regions, and the state appears to have increased food ration distributions to parts of the public (see one example here). That trade with China has continued to open up little by little in 2023 has probably contributed to food prices stabilizing as well. Still, current price levels remain far higher than normal. For a population’s whose margins are mostly very small, if it doesn’t amount to starvation, it means that an already difficult situation has gone from bad to worse.