By: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

Over the past few weeks, both Asia Press and Daily NK have reported the North Korean won depreciating against the dollar on the markets.

According to the figures from Asia Press, it seems the won first fell drastically, but that the initial FX-rise was a so-called “overshoot”, a disproportionately high rise of the exchange rate, but later corrected itself to levels more reflective of actual availability of dollars. The Asia Press index rose from 8,593 won/1$ on July 19th, to 9,463 won/$1 on August 6th, to 8,625 won/$1 on August 21st. Asia Press notes that the reason for the dollar appreciation is unclear, and speculates that it may be related to sanctions. That’s true, but it’s unclear what would have changed so suddenly and drastically in sanctions implementation as to cause a sudden rise of around ten percent. All in all, discounting the sudden and very temporary rise, the exchange rate rose by not even one percent.

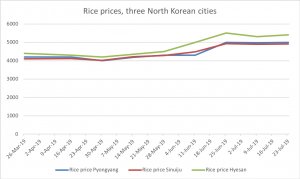

Reporting by Daily NK confirms the exchange rate spike reported earlier by Asia Press:

Daily NK conducted a market survey on August 6 that found the price of US dollars in North Korea was 7,850 KPW in Pyongyang, 7,880 KPW in Sinuiju and 7,900 KPW in Hyesan. The price ballooned some 800 to 900 KPW in just two weeks.

North Korea’s currency rate regularly sees significant volatility, but the last time the rate increased by 900 KPW in just two weeks was in 2015. During the second half of 2015, the North Korean authorities conducted harsh crackdowns on Chinese-made products and heightened international sanctions came into effect. The combination of these two factors caused the exchange rate to skyrocket more than 700 KPW.

There were even areas of the country that temporarily saw a spike to more than 9,000 KPW. In Rason, North Hamgyong Province, the exchange rate rose to 9,740 KPW on August 14 but has since retreated to between 8,500 and 8,700 KPW.

A Daily NK source in North Hamgyong Province said that the rising exchange rate may be related to stagnation in North Korea’s domestic markets. “The currency rate changes every day and it rose in August again,” he said. “The spike in the currency rate this year suggests that businesses aren’t doing so well and it may also be due to external factors.”

The source suggested that the external factors include the US-China trade war and China’s recent intentional devaluation of the yuan. For the first time in 11 years, the Chinese yuan broke past seven renminbi to the dollar on August 5.

Source:

USD – North Korean Won exchange rate spikes in North Korea

Kang Mi Jin

Daily NK

2019-08-22

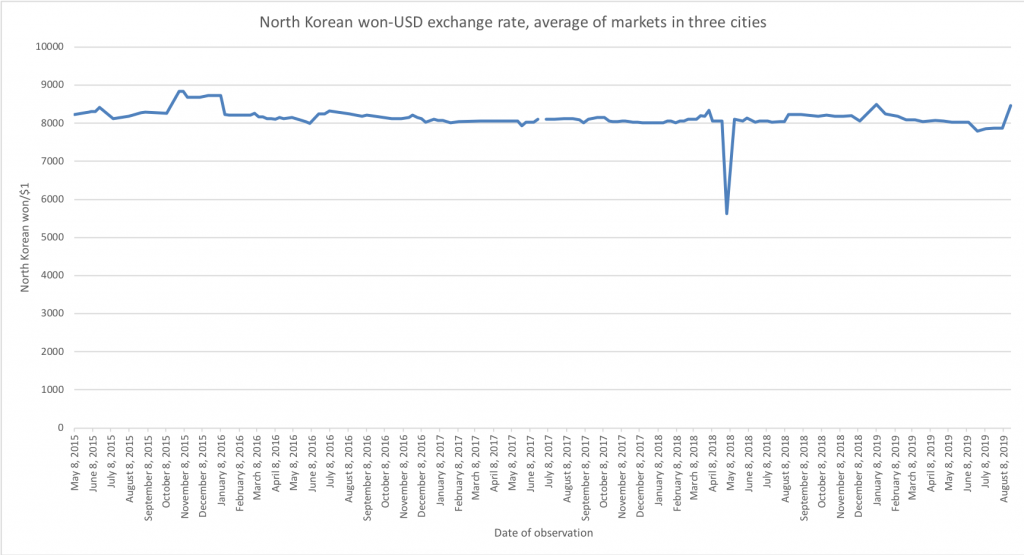

The FX-rate spikes aren’t reported in the Daily NK price index, so it doesn’t even appear in the broader exchange rate graph. The following graph shows the exchange rate from 2015 until Daily NK’s latest report, only a few days ago:

Graph 1. North Korean won/$1, 2015–August 2019. Graph by NK Econ Watch, data from Daily NK price index.

The won has depreciated against the dollar, for sure. Particularly in the short run. The past few weeks have seen slightly more volatility than usual. But still, in the big-picture context, things look fairly stabile.

Graph 2. North Korean won/$1, September 2018–late August 2019. Graph by North Korean Economy Watch. Data source: Daily NK.

A spike such as the one reported earlier in August can happen for many reasons. There is likely so little of US-dollars in circulation in North Korea that fairly minor changes can make a big dent in the market exchange rate. Communications function so poorly in North Korea that rumors spread easily with little possibility for quick confirmations or denials.

I and Peter Ward have previously argued, among other things, that the dollar isn’t a currency of general use in North Korea. The main holders of dollars are, most likely, state-owned corporations and other non-human entities. One move by a major holder could therefore have a significant impact on the market as a whole. The RMB has held completely stabile, so it’s very likely not a matter of any general stress on the markets. Had the source been something related to sanctions implementation, upped pressure, significantly changed expectations, or the like, we should have seen changes in the won-to-RMB-rate as well. As things stand right now, the market exchange rate does not look to be out of its normal range.