By: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

As I and Peter Ward discovered some weeks ago, the claim by Kim Jong-un that North Korea had its “best harvest on record” did not make it into the English-language summary of Kim’s plenum speech put out by KCNA. Several media outlets have picked up on this claim, and that is not surprising. Not even a year ago, last spring and summer, both the North Korean government and UN organs sounded the alarm bells that North Korea’s harvest was so disastrous as to suggest a famine might be looming.

So what happened?

First of all, it should be noted, as always, that one must be extremely cautious in studying data on anything related to the North Korean economy. Most people who follow North Korea are well aware of this but especially when it comes to an issue like this, one cannot be cautious enough.

I focus here on the claim by Kim that the harvest was the best “on record”. It may well have been a good harvest, or at least a much better one than anticipated. This seems to be the case. The only attempt I’ve seen at a numerical estimate comes from South Korea’s Rural Development Administration. They estimate that North Korea’s harvest grew by around two percent in 2019 over 2018. This sounds fairly plausible and could perhaps be explained by weather conditions unexpectedly improving, or fertilizer donations from China, and the like. Or the government and FAO’s projections were simply wrong from the beginning.

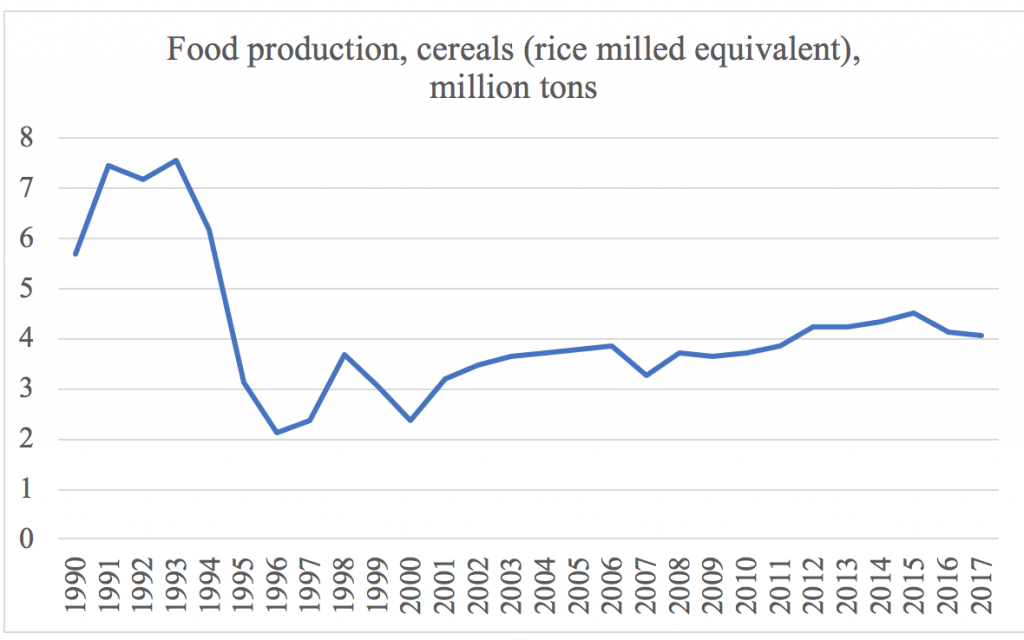

To understand why it is so unlikely that this year’s harvest would be the best on record, we have to look at what ‘the record” really says. The following graph shows North Korean harvest figures between 1990 and 2017, as recorded by the FAO. These figures are not independently recorded or verified but, to the best of my knowledge, generated by FAO in cooperation with the North Korean government, or provided directly by the government. Usually, that would be a problem, but here, it’s actually quite helpful since it helps us analyze the claim about the “record”.

Graph by NK Econ Watch/Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein. Data source: FAOSTAT.

I downloaded these numbers from the FAO database some months ago. For whatever reason, I’m unable to access the data at their website at this time of writing, and therefore, can’t fill in the data further back. This data also differs somewhat from other data on North Korean harvests from the World Food Program and FAO. Still, they match quite closely with other data the two organizations have published in recent years about North Korean food production. Again, keep in mind that this data is produced and published in concert with the North Korean government. In that sense, these numbers are the “record”.

Over the past few years, estimated harvests have gravitated between four and five million tons in milled rice equivalent. (You can read more here about what that actually means.) In 1993, North Korea’s record of harvests notes 7.5 million tons. Harvests hovered around 8 million tons in the 1980s – again, to the best of my recollection, as I can’t access the FAO statistics database numbers of North Korea at this time of writing.

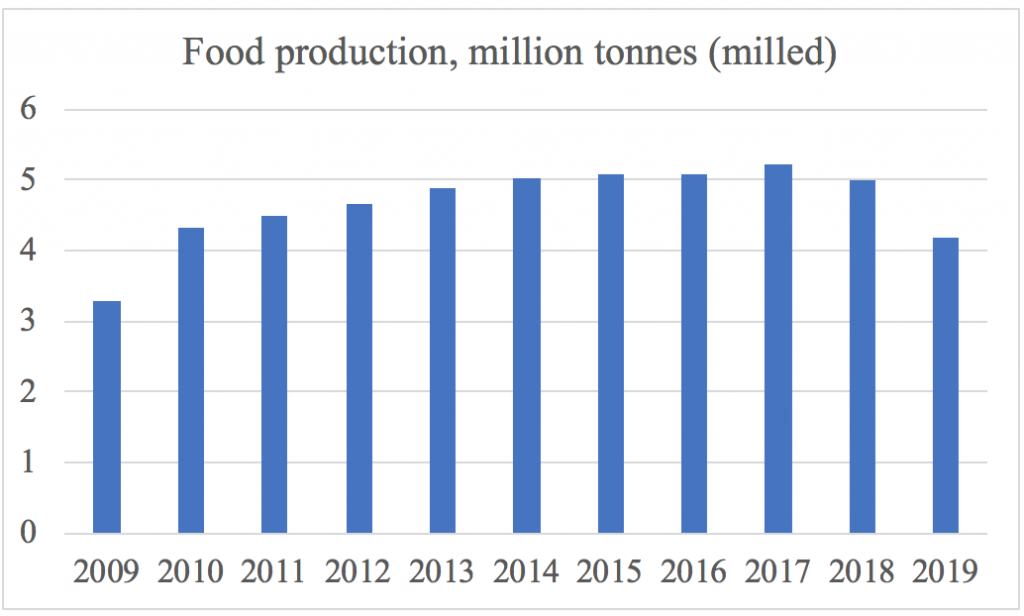

Graph by NK Econ Watch/Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein. Data source: WFP/FAO. 2019 is a projected figure.

For Kim’s claim to be true, therefore, this past year’s harvest would have had to go from around five million tons in 2018, to surpassing eight million tons in 2019. I am no agricultural economist, but Kim would likely need something like a miracle of nature for this to happen. I am not aware of North Korea’s landmass suddenly doubling, for example, or the amount of arable land increasing by one third overnight. Therefore, Kim’s claim is most likely, beyond reasonable doubt, simply not true. Note also that outlets such as Daily NK have reported that the government has taken predatory measures against grain trade as a result of what the outlet describes as “poor agricultural yields”.

In other words, there is very little to back up the claim made by Kim (and subsequently by North Korea-affiliated Choson Sinbo). This claim is a break with a pattern over the past few years, where North Korean media has been very frank – often, probably exaggerating – in describing difficulties and damage caused by flooding and inclement weather. There are several reasons why this may have changed with regards to the harvest. For one, food security a very basic need for any country. With bad food security, North Korea appears weak in the face of sanctions. It would hardly be the first time the North Korean government lied for strategic, propaganda purposes. It is also possible that harvests were much better than anticipated, and that Kim’s claim is merely a strong exaggeration. Perhaps “best on record” should be read as a superlative, rhetorical claim rather than a literal one. At the end of the day, we simply don’t know, and the ways of the inefficient North Korean bureaucracy are mysterious.