*All of the videos referenced in this post were deleted by YouTube in September 2017*

UPDATE 1(2016-2-23): The North Koreans have re-released the original documentary in Korean. Here are links to parts one, two, and three.

ORIGINAL POST (2015-3-20): Though Yeon-mi Park is arguably one of the most well-known North Korean defectors these days, for numerous reasons I have not devoted much of my time to her work. I was also surprised when Uriminzokkiri released two videos discredit Ms. Park (Video one in three parts is here. Video two is here). Maybe someday the North Koreans will catch onto the fact that these videos actually raise the status/profile of those they are trying to vilify, but in the meantime we can have some fun with them.

Ms. Park is the third North Korean defector (of whom I am aware) about which the DPRK has made these sorts of films. She now joins company with Shin Dong-hyuk and and Ma Yong-hae, though doubtless there are more.

The second video attacking Ms. Park was interesting to me due to the use of geography to try and discredit her story. So I thought I would write about what the video claims and examine whether its assertions hold up to some basic scrutiny. As was the case with the videos attacking Mr. Shin, the North Koreans appear to unintentionally verify some Ms. Park’s claims. So let’s begin.

The video states at the 3:33 mark:

In one of her lies, Park said that about eight kilometers from Hyesan in Ryanggang Province there is a “Juche Rock” in a peak of a mountain called “Kot-dong-ji (?)” in Komsan-ri (검산리). She said if you look down from that mountain peak you can see Pongsu-ri (봉수리) of Pochon County and [the] Amnok River. She said she took that route to escape.

But in fact there is a highway from Hyesan to Pochon County and just on its left side there is a small rock called “Juche Rock.” And if you look down from there the opposite side is Changbai County of Jilin Province, China.

On the far other side of [the] Amok River, you can see not the Pongsu-ri of Pochon County but Yonpung-dong, Hyesan City. So how on earth did she manage to find a mountain here in the region which she is said to have crossed at the risk of her life?

The video was indeed filmed in Hyesan, but unfortunately for the North Koreans, when I combine (a) data in the video with (b) administrative data published in North Korea with (c) satellite imagery, I get results that verify claims made by Ms. Park (as described in the video).

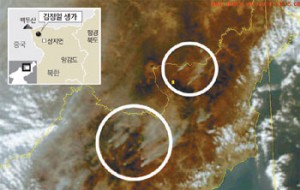

Here is a Google Earth satellite image of the area described in the video (where Ms. Park is alleged to have crossed the Amnok River):

To begin with, “Juche Rock” (41.449298°, 128.247329°) can clearly be seen on top of a mountain in Hyesan, Ryanggang province. I am not sure why the North Koreans wanted to bother disproving the existence of a mountain–especially if they are going to record a video from the top of it.

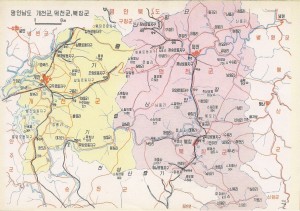

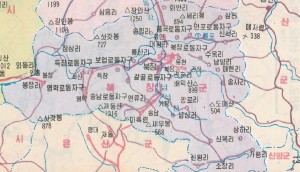

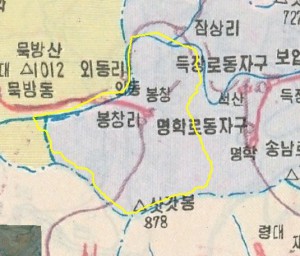

Secondly, “Juche Rock” is on the outer border of Komsan-ri:

Thirdly, later in the video (6:16), the North Koreans identify a house they claim was Ms. Park’s in Sinhung-dong, Hyesan City. Here is a satellite picture of that house (Marked in yellow: 41.397725°, 128.171969°):

I have no idea if the Park family actually lived here, but this house is exactly 8.48 km from “Juche Rock”. It’s a bit further on foot. So again, the satellite data is confirming what the video asserts Ms. Park claimed.

Finally, the point about the village to the north of “Juche Rock” being Yonpung-dong, Hyesan City, not Pongsu-ri of Pochon County, was the most difficult to for me to untangle. This confusion stemmed from two causes. The first was because Ms. Park is technically wrong about “Pongsu-ri” being the next village north of Juche Rock. The second source of confusion is because the North Koreans recently changed the border between Hyesan City and Pochon County and have apparently done some renaming in the process.

I have three maps (published in North Korea) that identify ‘Yonpung-dong, Hyesan City’ as ‘Hwajon-ri (화전리), Pochon County.’ You can see the area for yourself on Google Earth at 41.460212°, 128.231495°. Apparently sometime recently (I don’t know when), the North Koreans shifted the border of Hyesan City further north into Pochon County. At this time I suspect that Hwajon-ri was renamed Yonpung-dong. The only evidence that I have of the border change is a blurry map that the North Koreans produced to show the location of Hyesan’s new economic development zone. It shows the Hyesan border has moved north from its original location, however even it retains the name “Hwajon-ri.” The only source I have that the area has been renamed “Yonpung-dong” is this Uriminzokkiri video. But all of this certainly took place after Ms. Park had left the DPRK.

Here are approximate before and after pictures of the Hyesan – Pochon border changes:

To Ms. Park’s credit, however, there is an area just north of Yonpung-dong/Hwajon-ri called ‘Pongsu’ (봉수). It is not a ‘ri’, but it used to have a train station with the same name. The train station has since been torn down, but that may be the reason she remembers the area as “Pongsu.”

So to recap: The North Koreans published a video in which they called Ms. Park a liar (among other things) and used geography to prove that she had mislead people. The geographic points they raise in the video, however, tend to support comments Ms. Park is alleged to have made.

There is a separate question as to whether Ms. Park made the claims referenced in the video, and to that I have no idea. As I mentioned, I have not paid particular attention to her story.

However, I am delighted that digging into this video has taught me that the border between Hyesan and Pochon has changed.

There are other claims in the video that I don’t want to address because, frankly, I am not qualified–and it is Friday.