By Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein and Peter Ward

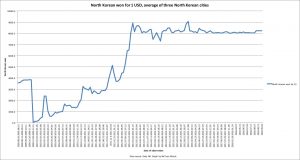

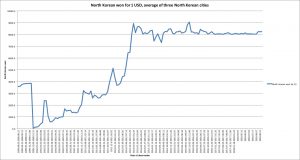

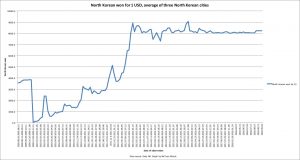

The stability of the market exchange rate for won-to-US dollars has been one of the most puzzling features of the economy over the past few years, and particularly so during the so-called period of “maximum pressure” and heavy sanctions by the international community. The market exchange has not once moved out of its ordinary – also remarkably stabile – territory over the past few years, as the following graph shows with clarity:

Won for USD-rates on the markets, 2009–September 2018. Data source: Daily NK. Graph: NK Econ Watch.

Thus far, to my knowledge, there have been two main, potential explanations:

(1) Maximum pressure is not having a meaningful impact on the North Korean economy as a whole. Even though it can’t export coal, minerals or textiles under current sanctions, its main sources for foreign currency revenue, the sanctions aren’t being enforced strictly enough to impact the economy as a whole, and foreign currency keeps flowing into the economy.

This explanation is pretty easy to dismiss offhand, since we know with more or less certainty that North Korea’s exports of these goods have plunged as Chinese sanctions enforcement has been fairly strict since the late summer/early fall of last year, even though it’s waxed and waned as it always does.

(2) The second explanation, most notably put forward by Bill Brown, is that Pyongyang is much better at monetary policy management than they’re given credit for. Chiefly (but not solely) through decreasing the amount of won in circulation, by giving state-owned enterprises (SOEs) smaller loans and credits in won, the government is able to keep the exchange rate stabile.

Speaking with my friend and colleague Peter Ward, a researcher of North Korean economic policy under Kim Jong-un and avid reader of North Korean economics journals, he explained a third possibility, partially in line with the latter hypothesis posed above. Ward visited North Korea twice in the past year, and was able to confirm many of the economic policy developments he had first detected in the literature from Pyongyang.

In short, Ward’s explanation is as follows: the main holders and users of foreign exchange in North Korea are not individual citizens, but state-owned enterprises, which legally (since 2013) use foreign exchange in transactions amongst themselves. The quantities of foreign exchange held by SOEs make them, and not the foreign currency markets that individual citizens access and use, the main determinant of the market exchange rate for foreign currency. Therefore, most of the foreign currency in circulation has been there for several years, not entering or exiting monetary circulation.

I asked Ward to share some of his thoughts with the readers of North Korean Economy Watch. Below is a brief Q&A of sorts.

Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein (BKS): first, when did this practice of SOEs trading in foreign currency become common and legally permissive?

Peter Ward (PW): probably around early 2013. This is when the “policy to make domestic production and exports one” came into force. The idea is to align domestic input prices for manufacturing, and consumer goods prices, with prevailing prices on international markets. This is literally what North Korean economics literature says that they aim to do, despite ostensibly being a socialist system in theory.

BKS: How is the FX-market price in North Korea determined? And where do the FX-market for SOEs and that for private citizens intersect?

PW: We don’t know, but one could imagine that there are major foreign exchange markets in North Korea – regional markets, both markets on the ground, so to speak, and between enterprises within regions. How does the center know the prevailing price? The regional price department of the regional People’s Committee price office and market management office (they may either be separate or the same) probably simply calls the local People’s Committee, who supposedly gathers this information from the local market management offices. At any rate, there’s reporting of the prevailing local exchange rate throughout the system.

Major enterprises will also know how much their inputs costs in foreign exchange, and a sense of how much their products would sell for on the world market. In that way, they’re able to assess the costs of their inputs in the world market (or at least China), and know how much they need to charge to make a profit or break even.

The market for individual citizens and SOEs intersect at several levels. SOEs likely source much of their inputs from wholesale markets, and from domestic private traders. They also obtain some of their foreign exchange from loans from private individuals. Private citizens can legally lend money to SOEs, but investments in SOEs by private citizens also happen, though they’re technically not legal, and both these investments and loans probably happen quite often in foreign exchange.

So the market price equilibrium happens through all these conduits, and as on any market, it is determined by countless instances of bargaining between traders, SOEs, and to a proportionally smaller extent, private citizens.

BKS: so where is the FX coming from, to begin with?

PW: if most inter-enterprise contracts and transactions are denominated in foreign currency, they’d be insulated from any sudden, exogenous trade shocks, such as sanctions. They’re still trading amongst themselves with whatever FX-holdings they have. For all intents and purposes, foreign currency inside North Korea is the principal legal tender – that’s what’s likely used for all major transactions inside the country, so exogenous shocks such as sanctions, from the outside, don’t necessarily impact the market price for foreign currency inside the country.

BKS: Is it likely, in your view and judging from your observations in North Korea, that the government maintains a price ceiling on the market exchange rate?

PW: Yes, it is. The government maintains price ceilings on a range of commodities, at least that’s what people inside the country say. They probably have an informal peg to the RMB, since China is their principal trade partner. It looks like it, but we don’t know for sure if they do. One possibility is that have significant cash reserves of RMB…

BKS: is it possible that China is simply helping North Korea keep the won stabile, by simply funneling RMB in?

PW: that’s certainly a possibility. The North Korean government keep a very close eye on the exchange rate, both in terms of physical cash in circulation and deposits in bank accounts, which SOEs have – both domestic and foreign currency bank accounts. They’ll keep a tight control over domestic currency-denominated loans to SOEs – that’s certainly one way of doing it. State banks will probably be encouraged to denominate such loans in foreign currency.

The government can also keep a pretty tight rope around money in circulation, since enterprises now have their own individual accounting system. The central government isn’t constantly borrowing money from the central bank to pump into SOEs, so the amount of money created by the central bank to lend to SOEs has gone down a lot.

That, at least partially, explains how the government manages to keep domestic currency circulation down. It doesn’t look like they’re printing much money overall, I saw bills from the pre-2009 currency re-denomination being used as late as July this year. And the highest denomination of North Korean won in circulation is the 5,000 won note, which has a market value of around 60 US cents, hardly appropriate for anything more groceries.