As an economist with an interest in North Korea’s monetary policy, banking, and capital markets, I have kept an eye on developments in North Korea’s payment technologies.

In this area I have previously posted about Koryo Bank Card, Narae Card, Kumgil Card, Ryugyong Commercial Bank ATMs, Jonsong Card, Golden Triangle Bank Card, Mirae Bank toll-road payments, e-commerce platforms Okryu, Sangyon, and Kwangmyong, and loyalty card programs at Haemaji Restaurant, Kwangbok Supermarket, and Moran Shop. There are, of course, other examples I have not blogged about.

Recently, however, the North Korean media has highlighted continued developments in this field, and I wanted to capture some of that information for readers here.

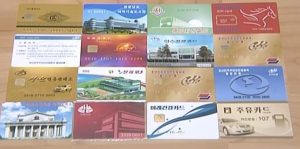

According to the North Korean media (2018-1-21), the Pyongyang Information Technology Bureau (평양정보기술국) and a subordinate organization, the Card Research Institute (카드연구소), appear to be developing cards for North Korea’s electronic payment system. Perhaps rather ominously, KCTV mentions that the agency is working to expand the use of cards with features like user identification. Below is a screenshot of some of the cards that they are producing.

Below are the names of cards as best I can tell (L-R,T-B):

1. Koryo Bank

2. South Hamgyong Province Sci-Tech Library Card

3. Pyongyang Metro

4. KoryoLink

5. ?

6. ?

7. Yaksu (mineral water) Payment Card

8. Jonsong Card

9. Soson? Gas Station

10. Jangmi Health Complex

11. Jonsong Card (Duplicate)

12. ?

13. Taedongmun Cinema?

14. ?

15. Mirae Health Card

16. “Juyu” Card

We already know that some of these cards are in use (KoryoLink, Jonsung) and others are apparently still in development (Pyongyang Metro Card) [As far as I am aware, people still pay for the metro with tokens]. Some of these are prepay cards for a specific service (KoryoLink for mobile phones), some are prepay cards for broader commercial transactions (Koryo Bank, Jonsong Card), others are probably a mix of loyalty and prepay cards.

A couple of recent articles in DPRK Today shed additional light these developments. The new smart card management system is called Ullim (Ulrim, 울림), presumably named after the famous waterfall in North Korea. The Ullim Network acts as a clearing house for outstanding fuel cards, bank payments, member card services, etc. The system is 100% locally developed (they claim).

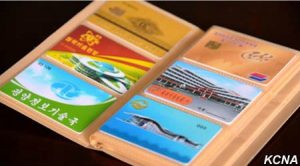

I am unsure how the Ullim Network is related to the Narae Network which is managed by the Foreign Trade Bank. Narae Cards are noticeably absent from any of the information put out by/on the Pyongyang Information Technology Bureau. Since all of these products seem connected to the Jonsong Card, under the control of the Central Bank, it may be that the Central Bank and the Foreign Trade Bank, which are still legally separate organizations last I heard, are developing their own separate e-payment networks. But foreigners buy KoryoLink cards (featured in this material) with Narae Cards, so I am not sure what exactly is going on. Maybe KoryoLink Cards for North Koreans (as opposed to foreigners) can be bought on the Jonsong card on the Ullim Network and foreign KoryoLink cards care bought with Narae cards issued by FTB? Maybe I am just overthinking all of this… Here are some other Ullim member cards featured in DPRK Today (KKG Bank was circled by me):

The cards featured in the lower image are (clock-wise from the top):

1. Koryo Bank

2. Jonsong Card

3. Pyongyang Children’s Hospital

4. Ryugyong Health Complex

5. Pyongyang Information Technology Bureau

6. Sci-Tech Complex

DPRK Today has also published information on the Pyongyang Bike Share Card, “Ryomyong” (려명자전거카드). This card is also part of the Ullim Network.

Recently, North Korean media also highlighted an electronic payment card for the Kwanghung Shop located in Rakrang District. It is unclear if the Kwanghung Shop card is related to the Ullim Network since it has not appeared in any of the marketing materials yet.

According to the report, the Kwanghung Shop card can be used offline and for online purchases. The shop also claims to offer delivery services for their goods if ordered online or by phone.

According to KCTV news (2018-2-23), the Energy Information Research Institute (전력정보연구소) under the Ministry of Electric Power Industry (전력공업성) is developing a payment card and mobile phone payment app:

The research discussed in the video is part of the National Power Management System (국가통합전력관리체계) named Pulyagyung (불야경/Bright Night Lights). The phone payment system displayed is a prototype remote electricity allocation system that allows retail electricity consumers to order electricity service from their mobile device instead of going to a physical office to have power allocated to a specific location.

Implications: There is a bright and a dark side to this technology. On the light side, we can group benefits to consumers: Payments are facilitated, savings options are increased, transactions costs are lowered meaning consumers benefit even as individual firms may earn float from the technology.

The dark side of the technology is of course how it can be used by the government for purposes of control/appropriation. In the old days, North Korea (and many other communist and developing countries) kept foreign currency out of the hands of their people through the use of Foreign Exchange Certificates (FECs). People had to change their foreign exchange into “green” money (for capitalist countries) and “red” money (for communist countries) to spend in local hard currency shops. This allowed the spenders to use their hard currency value to purchase imported goods while the actual hard currency paper stayed out of the hands of the people in the shops. This system was scrapped in the early 2000s. Electronic payment technologies mark a return to the goals of the FEC system…People can have foreign exchange balances to spend on imported goods at hard currency shops, but the actual paper currency remains on deposit at a bank.

This is bad news for North Korea’s black market and unofficial economy as well. With electronic payments it is harder to hide income and transaction history from the government (for tax/appropriation purposes). It would be very easy for officials in an anti-corruption investigation to pull up a spreadsheet of ones legal income and transactions to see if there is a substantial mismatch with your assets and standard of living.

Anyway, we will see how this develops. There is still a great deal we do not know.