By Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

(Updated 27/2: see below for clarification on the nature of the North Korean memo; the appeal was never meant to be publicized. Another minor clarification below done on 11/3.)

During the past week, both the UN and the North Korean government has made claims that its food situation is bad enough for the country to need international emergency aid. AP:

U.N. spokesman Stephane Dujarric said Thursday that food production figures provided by North Korea show “there is a food gap of about 1.4 million tons expected for 2019, and that’s crops including rice, wheat, potato and soybeans.”

Dujarric says the U.N. has “expressed and will continue to express our concern about the deteriorating food security situation” in North Korea.

He says the U.N. “at various levels” is consulting with the North Korean government “to further understand the impact of food security on the most vulnerable people, in order to take early action to address the humanitarian needs.”

A few days ago, North Korea’s UN ambassador distributed a memo (presumably to UN officials) saying that because of sanctions and unusually warm and dry weather last summer, this year’s harvest was worse than expected. NBC reported some of the contents:

Kim’s claims are difficult to verify, and his government has not always been a reliable source of internal statistics. He said a food assessment, conducted late last year in conjunction with the UN’s World Food Program, found that the country produced 503,000 fewer tons of food than in 2017 due to record high temperatures, drought, heavy rainfall and — in an unexpected admission — sanctions.

The food agency could not immediately confirm that the organization conducted an assessment with North Korea or the conclusions the country shared in the memo.

In a plea for food assistance from international organizations, however, the memo states that sanctions “restricting the delivery of farming materials in need is another major reason” the country faces shortages that has forced it to cut “food rations per capita for a family of blue or white collar workers” from 550 grams to 300 grams in January.

“All in all, it vindicates that humanitarian assistance from the UN agencies is terribly politicized and how barbaric and inhuman sanctions are,” the memo says.

The memo is worth reading in its entirety.

There are a lot of things that are strange about this memo and its contents. I’ll try to deal with as many of them as possible here. But first: how bad is the food situation, really?

This question is virtually impossible to answer accurately, because no one really knows how much food is being produced in North Korea. The World Food Program that works with the North Korean government to estimate harvest yields does what it can under difficult circumstances to accurately measure harvest yields in the country. But these measurements are severely restricted by the fact that much of food supply and production in North Korea still completely lacks transparency. For one, we know that most citizens get the majority of their food through state-administered private markets.

International agencies, however, still cannot survey these markets or study their role in food provision, because the government’s attitude to the market’s very existence remains somewhat ambivalent. The crop surveys conducted with the North Korean government simply cannot answer how much food is available throughout the system, because the markets, the most important node, cannot be assessed and studied accurately. Surveying the markets would let the WFP study the situation in its entirety, since that way, they could take into account both imports, private plot farming, and the like.

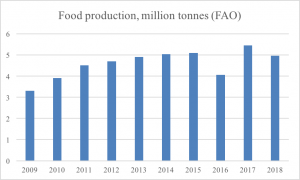

But taking the numbers provided by North Korea and the UN at face value, it’s clear that if these numbers reflect reality, domestic food production is down since the past couple of years, but not by disastrous amounts. There’s no second “arduous march” lurking behind the corner, judging from these figures. In fact, harvests have been growing for several years, largely thanks to changes in agricultural management under Kim Jong-un.

Food production in North Korea, in millions of tons. Harvest data is usually given in “marketing years”; figures here partially based on full-year estimates earlier in the respective year. Data source: World Food Program/Food and Agriculture Organization. Graph by North Korean Economy Watch.

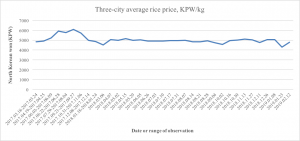

Moreover, and perhaps most importantly, market prices for rice have remained stabile. So the markets don’t seem to think there really is a true food shortage coming, even though things do seem to have gotten more difficult due to the drought. I cover this in more detail in this post, but the following graph speaks its clear language.

At the very least, had there been major signs of stark shortages, it would have been visible in the price data. Reports from North Korea do confirm that food production seems to be down overall, but remember, that’s from a fairly high level and after several years of increases. Over the past few years, the North Korean government and UN agencies have made similar appeals, but in the end, fortunately, no major crises seem to happen.

The strangest part about the North Korean memo is that it speaks of reduced rations of grains to “a family of blue or white collar workers” as a result of the drought and sanctions. The thing is, only relatively few people and almost no civilians in North Korea actually get their food through these government rations. The Public Distribution System (PDS, or 식량배급제도) essentially only operates for the military, shock work brigades (돌격대), and within the judicial administration (more accurate would be to say “government administration”; this is a rather nebulous category in North Korea, including large numbers of civil servants within both the central state, local government level, and policing organs). So this “white or blue collar worker” likely wouldn’t necessarily get her or his rations anyway. As far as we know, they’d go and buy their food at the market with cash instead, in most cases.

It’s often believed that North Korea doesn’t admit weaknesses such as food shortages out of political principle, but over the past few years, the government have been very public with claims of shortages on the horizon, and in asking for aid. Not because the state can’t afford to compensate for the shortfall, but because it simply has other priorities.

Reading the North Korean memo, it’s easy to suspect a connection with next week’s summit in Hanoi and the sanctions situation. By getting news stories out that civilians are starving because of sanctions – a highly questionable claim of causality – the North Korean government may be trying to create more bad press for the sanctions as such.* How can the US argue that they should be preserved, if they’re even preventing North Koreans from getting access to food? There are certainly troubling humanitarian aspects of the sanctions, but it’s difficult to imagine how they could have directly caused the harvest to dwindle.

None of this is to say that North Korea shouldn’t get food aid, that’s a different question. But the government’s basis for the appeal is rather dubious, to say the least. Hopefully, one day international humanitarian agencies will have good enough access to actually get to evaluate the country’s food situation, without constraints.

*Apparently, the memo from North Korea’s UN ambassador was leaked, not intentionally distributed. A person with insight into the issue and appeals process tells me the appeal was never meant to be publicized. This makes my interpretation above far less likely, though the direct impacts of sanctions on the harvest is still questionable.