By: Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

At this point, it seems unlikely that not a single case of the coronavirus would have reached North Korea, despite government media claims. The border to China is quite porous even when controls are tight, and the provinces bordering North Korea had seen, as of last week, some 200 cases. The government has ordered schools shut for one month starting five days ago, on February 20th. Unsurprisingly, it has taken special care to protect Pyongyang from the virus, and face mask distribution goes first to the one percent.

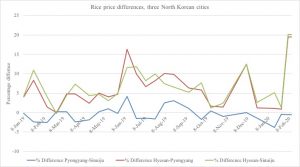

The economic effects of all this are very troubling. As this blog has previously noted, markets and society overall seem to be taking the border closure much more seriously than sanctions, and have reacted with much more anxiety than when new rounds of sanctions measures have been levied by the international community in the past. Prices have climbed quite drastically, as we shall look at in some detail in this post. They have risen by much more in Hyesan than in the rest of the country, which tells us something interesting about the government’s internal controls. That differences in market prices are increasing could be a sign that internal controls on travel across provincial boundaries are being enforced quite effectively. When traders cannot as effectively move their goods to where demand is the highest, prices will increase. One also has to bear in mind that Hyesan is very dependent on trade with China to begin with, and we should therefore expect prices there to increase disproportionately.

(My apologies for the awkward look of the graphs — please click for full size!)

In normal times too, prices tend to be higher in Hyesan than in other cities. But usually not by that much. Notice what happens around January, though: prices skyrocket all over the country but they do so by much more in Hyesan.

This is particularly evident when we look at price differences. Normally, prices are between 5–10 percent higher in Hyesan than in both Pyongyang and Sinuiju. Since the border closure, however, they have gone beyond 20 percent over both cities, according to price observations from the past few weeks.

Again, the border closure to China may be a central part of the explanation. But rice itself isn’t typically a good that North Korea relies so much on Chinese imports for. We don’t know the precise proportions, but likely, most rice consumed in North Korea in an ordinary year is grown within the country. A likely conclusion is, therefore, that the closure of provincial borders within North Korea is being enforced with some efficiency, making it much more difficult for market traders to transport goods such as rice between different markets in the country. This adds to the already stark economic difficulties from the closure of the border to China. Many other prices have risen drastically as well: gas prices in Hyesan are now 46 percent higher than in late December of last year, and 38 percent higher in the country as a whole. The government has attempted, reportedly with some success, to institute price controls on the markets, but as the story goes with such state attempts in general, they are unlikely to last as black markets arise to respond to shortages.

Again, the border closure to China may be a central part of the explanation. But rice itself isn’t typically a good that North Korea relies so much on Chinese imports for. We don’t know the precise proportions, but likely, most rice consumed in North Korea in an ordinary year is grown within the country. A likely conclusion is, therefore, that the closure of provincial borders within North Korea is being enforced with some efficiency, making it much more difficult for market traders to transport goods such as rice between different markets in the country. This adds to the already stark economic difficulties from the closure of the border to China. Many other prices have risen drastically as well: gas prices in Hyesan are now 46 percent higher than in late December of last year, and 38 percent higher in the country as a whole. The government has attempted, reportedly with some success, to institute price controls on the markets, but as the story goes with such state attempts in general, they are unlikely to last as black markets arise to respond to shortages.

Tags: Corona