By Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

One of the more puzzling issues through the “maximum pressure”-period and harsh Chinese implementation of international sanctions on North Korea has been the lack fo significant changes in the market exchange rate between the won and the dollar. For a number of apparent reasons – lack of inflow of hard currency being the most significant one, as North Korea’s exports have dwindled – we should have logically seen the exchange rate appreciating, and the dollar becoming more expensive. This largely hasn’t happened.

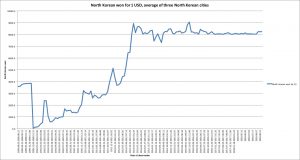

The won is still remarkably stabile, but over the past few weeks, it’s gone up to higher levels than at any point through 2017 and 2018. An average of the three cities reported in Daily NK’s four most recent observations show that the dollar trades for an average of about 8237 won, the highest observation that I can find in my dataset (based on Daily NK price reports) since the summer of 2016.

Won for US-dollars at market rates, 2017–September 2018. Data source: Daily NK. Graph: NK Econ Watch.

It’s doubtful whether this suggests any significant change in market conditions. Currencies, after all, fluctuate, and this change isn’t all that great. The won is up by less than 200 since the previous observation, from 8041 on July 31st. That’s not a massive change, or beyond the scope of normal currency fluctuations. In a bigger-picture perspective, things still look remarkably stabile, as the graph below shows. Looking at the won-USD-exchange rate since 2009, it’s still very much hovering around 8000, perhaps and highly speculatively a currency peg the North Korean government has chosen, and is able to keep up through means that remain unknown.

Still, a number of things may be happening here. The most obvious factor to consider is whether the current stall between the US and North Korea in negotiations is causing people to hoard dollars, anticipating further restrictions in trade and currency inflow. Off the top of my head, this seems unlikely. If the won-USD-market exchange rate didn’t move much when North Korea was being slapped with sanctions against all of its crucial export goods, I doubt that a lack of diplomatic movement could move the exchange rate to higher levels than during, say, the summer and fall of 2017, when tensions were really ramping up.

It is more likely that domestic conditions are behind the increase. For example, border controls on trade and smuggling reportedly tightened on the Chinese side around mid-August. On the North Korean side of the border, too, news reports indicate that security has tightened as the 9th of September approaches, North Korea’s 70th founding anniversary. It’s also possible that the government’s generally increased demand for resources around the holiday has impacted the currency market.

Alone, this increase says little. Should the USD consistently keep appreciating on the markets, however, that would suggest more serious and prolonged difficulties for border trade and economic conditions overall.

Tags: 2018 sanctions